Dr. Alan Verde: Marine Scientist and professor

Tell us about yourself! How did you begin diving/snorkeling?

I have always been connected to, and completely fascinated by, the ocean realm my entire life as far back as I can remember. When I was a kid (5-6 yrs. old) in the Philippines, I clearly remember playing with my brothers in our parent’s fish farm next to an estuarine river, fishing, and digging for crabs. During one of my excursions of solo swimming in the middle of the river, I happened to find a dead crustacean that was stuck between bamboo slats of a fish weir. I vividly recall looking at it and seeing the back half of a shrimp and the front half of a “praying mantis” with its lethal arms extended. It was not until my Marine Invertebrate Zoology course in Hawaii during my sophomore year in college that I found out what that organism that I witnessed in my childhood was a mantis shrimp! I obtained my Open Water Diver certification while I was a junior in high school before the recreational diving industry really exploded; four of us contracted a YMCA diving instructor to teach us during weekends during the fall and we did our check out dives with several inches of snow on the ground. We had to throw rocks to break up the layer of ice on the quarry. It certainly was a very cold and numbing experience, but one that I look fondly back on since that is how the underwater world became accessible to me for the rest of my life. I have had the great privilege of being able to travel to many places in the world and dive as an undergraduate, graduate, post-doctoral, and now as part of my job as a professor of marine biology at Maine Maritime Academy (MMA). Arguably, I have the best job at MMA since I get to teach interesting courses on topics that I really enjoy (Marine Zoology, Physiology of Marine Organisms, Symbiosis, Scientific Diving…). During Spring Break in March, I co-teach a Master Diver course that has gone several times to Bonaire and the Philippines. The students really enjoy the trip since they do lots of diving in tropical waters (for many of them, it is their first experience in warm waters), learn a bit about the local culture, and get to temporarily run away from the bitter February cold that Maine has to offer!

Can you share more about your work on invertebrate symbiosis and biology?

I specialize on the mutualistic symbiosis (tightly coupled interaction between completely different organisms) that takes place with cnidarians hosts (such as corals, anemones, jellyfish, gorgonians) and microscopic unicellular algae that reside intracellularly within the cells of their host. Most of the time, it is beneficial to both algae and cnidarian (mutualism) but every so often, when the environmental and physiological conditions are suitable, the association my convert to parasitism such that there is a sliding scale between positive and negative interactions. This shifting system really intrigues me since I investigate how the environment that an organism finds itself triggers/controls/regulates the physiology and biology of the organisms. Consequently, I am a person who is very interested in how an organism responds to changes and adapts to a constantly fluctuating natural environment. I have been able to work with organisms in both the tropics and temperate oceans and I really enjoy both the similarities and contrasts between the two very different situations and how the organisms deal with it. In the tropics, I have been able to conducted studies on corals, jellyfish, sea cucumbers, damselfish and anemonefishes whereas in the temperate environment, I have done research on anemones, sea cucumbers, and octopuses. Looking back on the past research projects involving both undergraduates and graduate students in the field to collect information, data analysis, and writing of the manuscripts for publication is very rewarding to me as a professor and scientist.

How did you become interested in studying endosymbiosis, symbiosis, and octopuses?

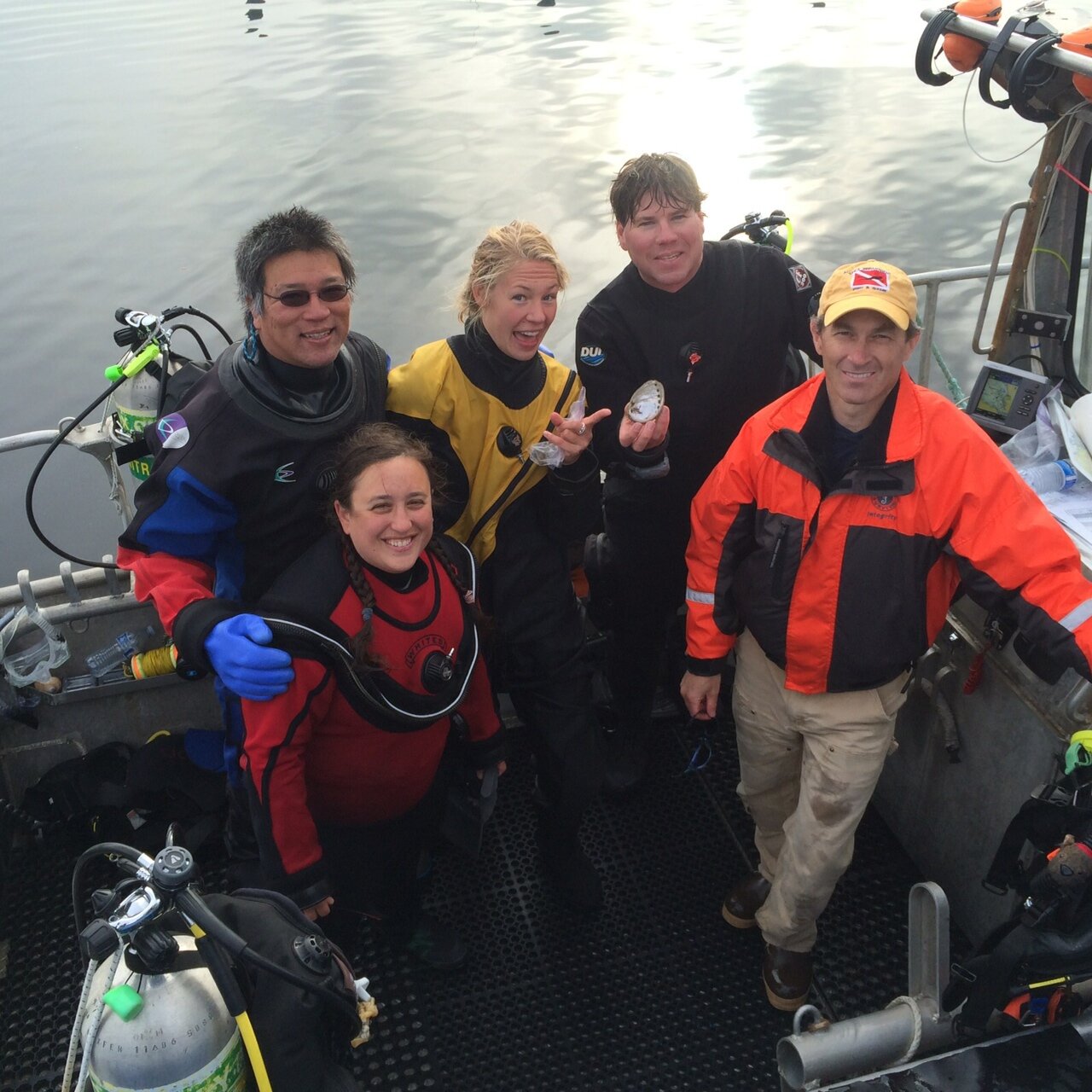

Preparing a time-lapse camera to document an octopus hiding in a bottle with Dr. Kirt Onthank and Dr. Jim Nestler at RBML.

I was very fortunate to spend several summer months at the Rosario Beach Marine Laboratory (RBML) in Anacortes, WA, as an undergraduate student majoring in biological sciences. I was taking Marine Ecology at the time and the course introduced me to various symbiotic associations between organisms in the ocean, including endosymbiosis which involves microscopic algae that live inside (hence the term endosymbiotic) the cells of the host animal. Afterwards, I stayed and conducted my senior research project on the sea anemone Anthopleura xanthogrammica which contains unicellular green algae within its cells…and that is how I got started on the “dark path” conducting research on cnidarian-algal symbioses. Immediately after graduation, I was invited to spend the summer working on corals in the Gulf of Eilat, Israel, which was a completely amazing experience for a 21 year old getting to dive in tropical waters and also travel to a different country to become exposed to their culture and food. The research on the physiology of symbiotic corals, comparing shallow versus deep colonies, really was what convinced me that this was the right path for me. Subsequently, as part of graduate school for my Master’s program, I followed it up by looking at the carbon flow between the host anemone Anthopleura elegantissima and two different algal symbionts, a brown dinoflagellate and a green chlorophyte, that is intracellular in the cells of the anemone. What was very interesting is that there are so many differences between the two algal symbionts in terms of photosynthesis (CO2 fixation), growth rates, and amount of carbon that is translocated (transferred) from the algae to the anemone host cells. After I finished my Master’s program, I moved from WA to FL and started my doctoral program at Florida Institute of Technology to work on kleptoplasty (“stealing of chloroplasts”) in nudibranchs that are found in the FL Keys. However, due to unforeseen circumstances, instead of working with nudibranchs that contained chloroplasts in their digestive track, I elected to go back to RBML and work on the A. elegantissima-dinoflagellate-chlorophyte symbiosis over the course of 1.5 years and investigate the effects of temperature, light intensity, seasonal change, and anemone size on the photo-physiology of the anemone-algal association. Subsequently, I went on conduct research for several years on anemonefish and their host anemones in both Papua New Guinea and the Philippines on how carbon and nitrogen flow and are transferred between the algae, anemone, and anemonefishes. My current interest in octopus biology, ecology, and physiology of both Octopus rubescens and Muusoctopus leioderma evolved from helping to collect octopus and deploy cameras to try and obtain video documentation of the octopus leaving/entering their dens.

What do you wish everyone knew about the ocean?

Unfortunately, humans are ecosystems engineers and like to modify the environment to suite their demands. From the extraction of raw materials, use of fossil fuels, fabrication of chemicals, modifying the landscape…we are the only species that has heavily impacted (and not in a favorable way) in multiple ways, the terrestrial environment and that also translates to modification and changing, in multiple ways, of the marine environment to its detriment. The net effect of all of this ecosystem engineering is that the global weather patterns, major oceanic currents, and marine chemistry are changing. Climate change, whether you believe it or not, is a real and growing threat to our future enjoyment of the marine environment and each of us must do our part to mitigate these long-term changes. The oceans were once thought to be so vast that it could not be affected…but that is definitely not the case, based on a multitude of studies.

With your work, what do you hope to accomplish/discover/learn? Or with your work, how does it apply to our lives?

Deep down, I am an experimental marine biologist so I like to tinker with what factors affect marine organisms especially organisms that involve symbioses which is pretty much all multicellular organisms on the planet. Studying these associations and how they are affected by their environment can provide key insights into how the association is controlled and regulated so that we can see if that is also what is happening in different symbiotic relationships, not only in the aquatic realm, but also in the terrestrial environment. Being able to compare and contrast the similarities and differences between various very different organisms provides us with a much broader knowledge base on which to make predictions of how these organisms may adapt to the changing environment that surrounds them.

What is some of the best advice you have received from mentors? What advice do you have for young scientists, artists, and explorers?

If you want something bad enough, you will do whatever it takes, jump through the hoops, make the necessary sacrifices, to achieve your goal and make it a reality. What does this bit of advice really mean to young scientists, artists, and explorers? If you would like to become a marine scientist (or whatever job title you want) bad enough, you will take the math, physics, chemistry classes to help you prepare, finish your college education with your best efforts, and seek out opportunities to build your talents for your role as a future marine scientist…or whatever plans you have for your life.

Please share a favorite memory from your work!

I really enjoy watching the behavior of anemonefishes as they go about their daily lives around their sea anemone host. It is so much fun to see individual anemonefish as they interact with other fishes, be it other anemonefish or other fishes such as damselfish and wrasses that they chase away from their anemone or clutch of eggs to keep them from being eaten. Another favorite memory is also collecting the anemonefish for laboratory studies so we would wail till about an hour after the sun set and we would go diving and hand collect the sleeping anemonefish as they are tucked away in the tentacles of the anemone. Sometimes an anemone had a fish or two and other times, you would not fine any anemonefishes so it was always exciting to reach into an anemone with your hand and feel around to sense if a fish was present or not. Then the real fun starts as you try and capture the anemonefish before it wakes up and makes a mad dash for a nearby hiding place in the reef.

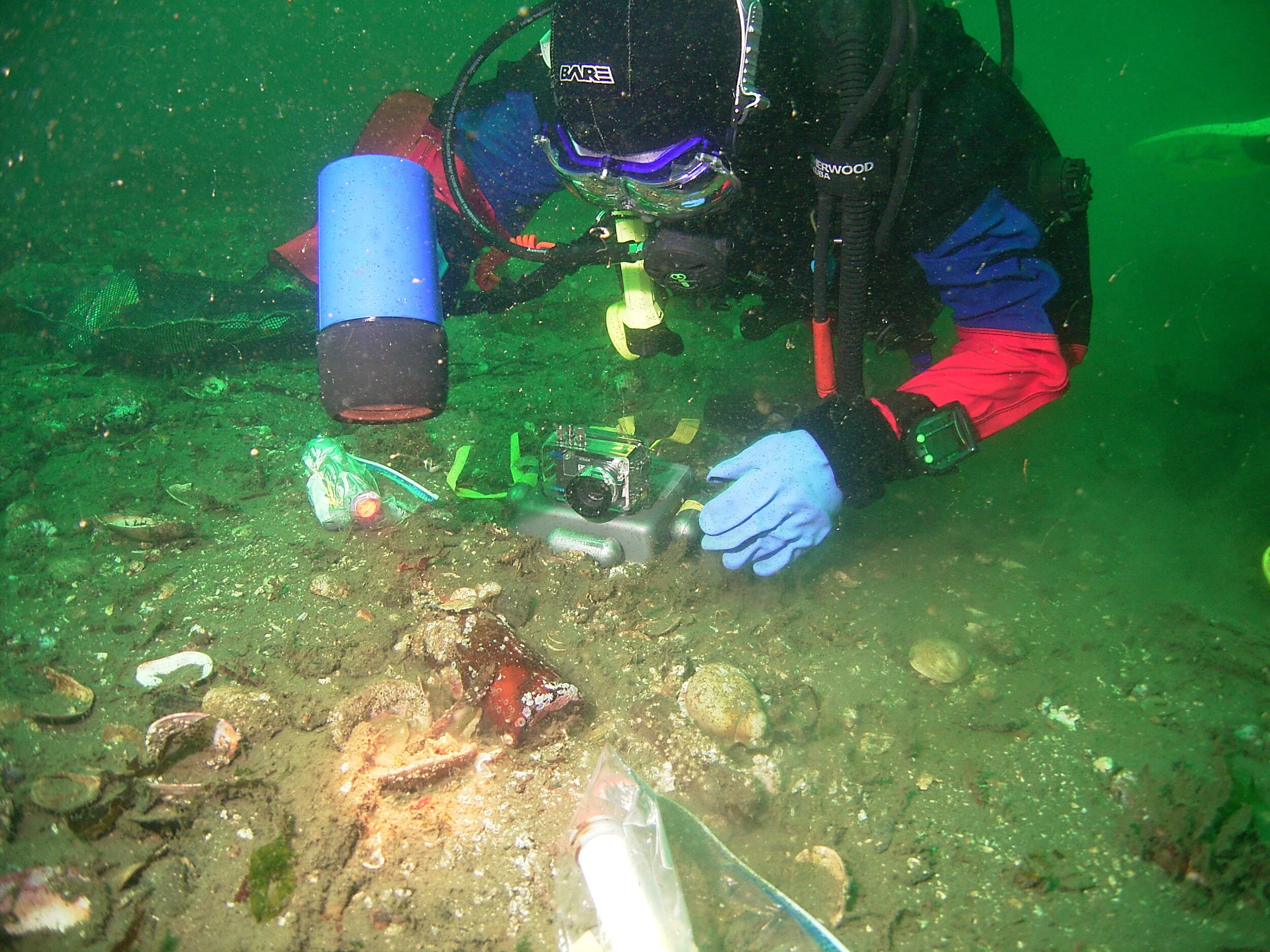

Diving with buddy Jillian Perron looking for ruby octopuses at Admiralty Bay, WA. Photo by brother Ray Verde.

Please share a marine scientist, explorer, artist, role model whose work you admire! Or someone you think might be interested in sharing their work with us.

One marine scientist that I admire is Ove Hoegh-Guldberg who is one of the primary “movers and shakers” regarding raising awareness of the effects of global climate change on the marine environment, especially the tropical reefs in the Pacific. I met Ove when I just graduated from college and he was a Ph.D. student at UCLA and we were the research assistants on a coral physiology project in the Red Sea portion of Israel. Over the course of 48 hours, we would have to go out every two hours to collect coral samples and freeze them so during the night, we would just sleep on the beach, wake up and get samples, then attempt to go back to sleep on the beach before the next collection time point. We had conversations about a lot of things during those 2 months in Israel and I have been in awe at his meteoric rise in the scientific community and ultimately in the international stage once he graduated from UCLA and went back to Australia. It is interesting to meet, work with, and getting to know a person before they become famous within the coral symbiosis community and subsequently, well known throughout the world regarding their work to help governments implement policy regarding climate change issues.

Thank you for sharing with us! Keep inspiring students with your research and contributing to our understanding of the changing ocean.

We always love to be introduced to new ocean explorers. If there’s someone you’d like to see an interview from, send us your ideas!