Dominic Sivitilli: Phd student and octopus scientist

Tell us about yourself. How did you begin scuba diving and studying the ocean?

I grew up on a farm in rural Washington. My backyard was a forest that I could wander for hours. It was here that I began to appreciate the complexity of life and the connection we share with it. I moved to Seattle in 2012 when I became a student at the University of Washington. I studied biology and psychology, and developed a passion for animal biodiversity and behavior. The body and mind have evolved into so many different forms, all with unique ways of perceiving and experiencing the world. I started diving in 2016 when I became a graduate student. There is incredible biodiversity in the ocean that seems so inaccessible until we dive and see it for ourselves.

Can you share more about your work?

While our brain is highly centralized like other vertebrates, most of the octopus’ brain exists within its arms. The octopus therefore uses a completely different strategy for sensing, thinking and moving. To study this, I create puzzles that the octopus must solve using its arms. I then analyze the strategies they use to do this, revealing how the octopus’ arms explore and interact with the world.

I'm also involved in the Astrobiology Program at the University of Washington, a community of researchers dedicated to understanding life as it might exist beyond earth. As a uniquely intelligent invertebrate, evolutionarily distant and with an entirely different body plan from ourselves and other vertebrates, the octopus serves as a model for other forms intelligence might take in the universe.

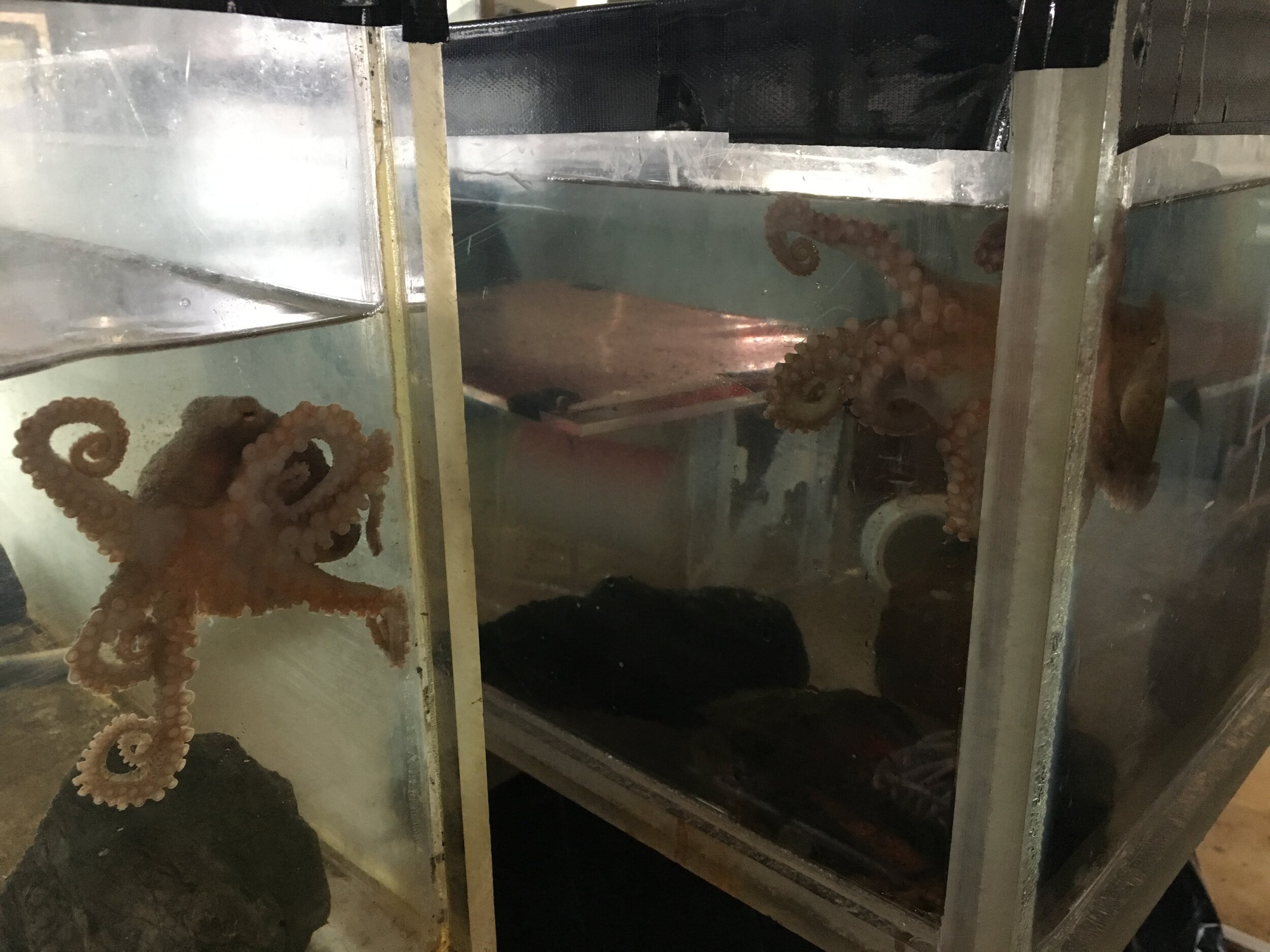

Most of the octopus’ brain exists within its arms and suckers.

How did you become interested in studying octopuses?

The field of psychology focuses mainly on vertebrates, like ourselves, other mammals, reptiles, birds, amphibians, and fish. However, vertebrates only make up a small fraction of animal life, while most animals are invertebrates. I felt like I needed to look beyond vertebrates if I wanted to understand the mind. I visited Friday Harbor Labs one summer to study invertebrates. I was surrounded by so much biodiversity, so many varieties of body plans and of behavior! The octopus was the most fascinating to me. It was so curious and intelligent, yet so alien.

What do you think everyone should know about octopuses?

The octopus and other cephalopods have the most complex brains of all the invertebrates, and most of the octopus’ brain exists within its arms and suckers. Each sucker is extremely sensitive, with tens of thousands of mechanical and chemical receptors. A single sucker is about a hundred times more sensitive than a human fingertip with the added ability of taste.

Octopuses are mesopredators, meaning they are both hunters and hunted. They have incredibly complex camouflage abilities which help them hide from their predators and from their prey while they are out hunting.

Octopuses are also very devoted mothers. When a female lays eggs, she will guard them until they hatch, then she dies. She won’t leave, even for food. In the giant Pacific octopus, this can last for months.

What do you hope to accomplish or learn through your work?

By studying the octopus, I’m hoping to understand how a completely different form of body and mind experiences and interacts with the world. The ocean is home to incredible biodiversity and a huge range of anatomical and behavioral complexity. What else is living and thinking in the alien world of the ocean, and what can this tell us about ourselves and life on other worlds?

Dominic with Neo the octopus.

Please share a favorite memory from your work!

My favorite part of my work is forming a bond with my octopuses. They all have different personalities and it’s incredibly rewarding getting to know each of them individually and to build trust with them. They are also very curious and playful, so it is fun to give them things to explore and play with.

What advice would you like to share with young ocean scientists, artists, and exploreres?

One of my professors stressed an important point that made an impression on me. Biodiversity is declining. This is likely the last time in our life that the earth will be as diverse as it is. Now is the time to appreciate it, understand it, and to protect what’s left.

Thank you for sharing with us and contributing to our understanding of the octopus!

We always love to be introduced to new ocean explorers. If there’s someone you’d like to see an interview from, send us your ideas!